Understanding the Components of an AI Tech Stack

Introduction and Outline: How the AI Tech Stack Fits Together

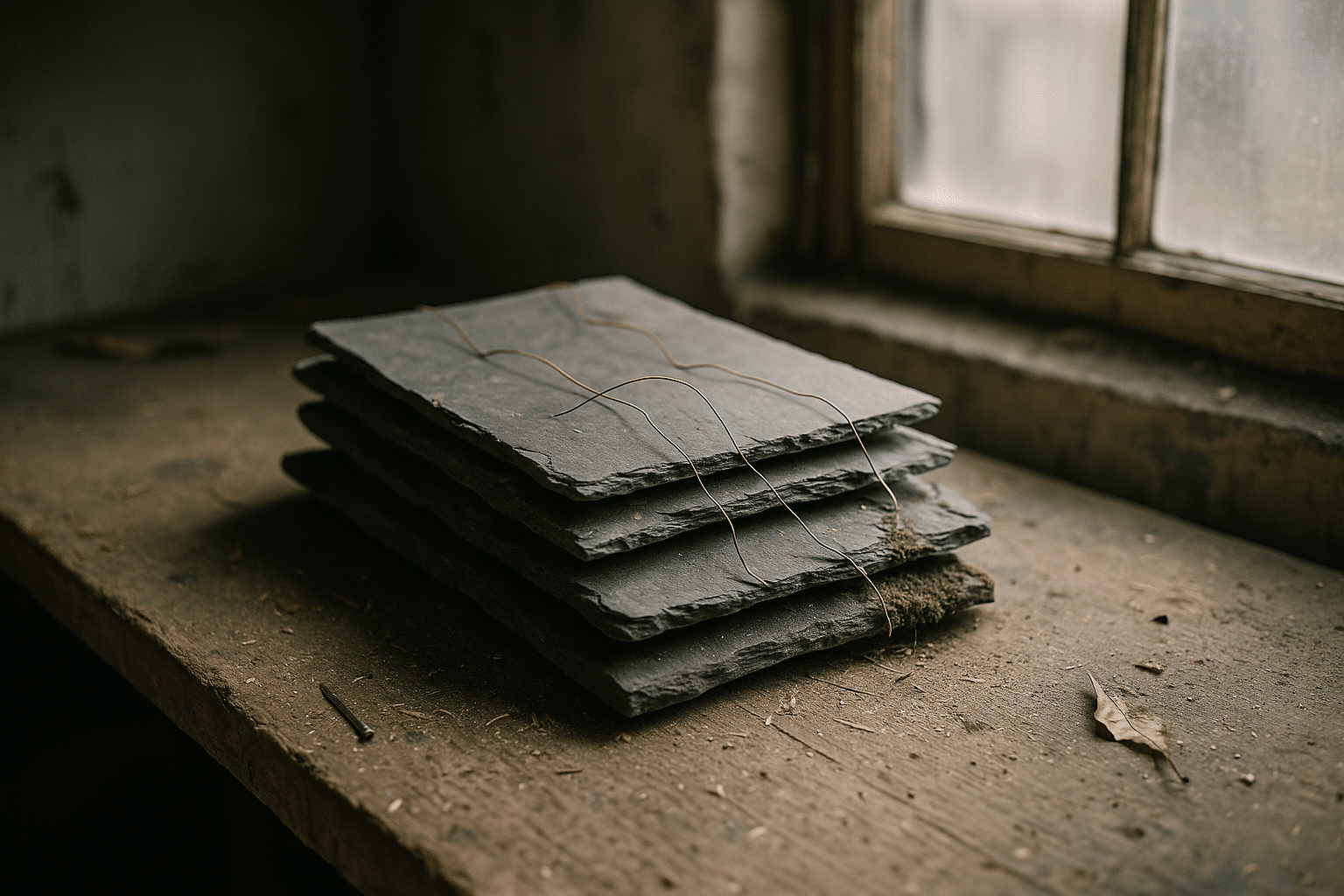

Artificial intelligence is easiest to understand as a layered system: data at the foundation, learning methods in the middle, and applications at the surface. Machine learning offers the general toolkit for turning data into predictions, neural networks provide a flexible pattern-recognition engine, and deep learning scales that engine into many stacked layers that learn rich representations. Think of it like sedimentary rock: layers formed over time, each compressing insight from the one below it, together creating a sturdy structure that holds up real products.

Before diving into specifics, here is the roadmap for what follows and how it supports real-world decisions:

– Machine Learning foundations: problem framing, features, training, and evaluation for structured and unstructured data

– Neural Networks: how differentiable layers, activation functions, and optimization interact, plus when to prefer them over classic methods

– Deep Learning: representation learning at scale, common architectures, and operational trade-offs

– Building a cohesive stack: data pipelines, training workflows, deployment, monitoring, and responsible-use checks

– A conclusion with a compact action plan for teams and individual practitioners

Why this matters now: data volumes continue to rise, sensors proliferate, and software increasingly adapts to users in real time. Teams that understand the differences among learning approaches make better choices about cost, latency, maintainability, and accuracy. For example, a straightforward classification problem with clean tabular data may be handled effectively by a compact model that trains in minutes, while a perception task involving images or audio often benefits from deeper architectures with millions of parameters and higher compute needs. The point is not to crown a single approach, but to select an approach that matches constraints: available data, labeling budgets, explainability requirements, and deployment environment.

Throughout the article, you will find comparisons and practical heuristics rather than one-size-fits-all rules. We will reference common failure modes (overfitting, covariate shift, stalled learning) and discuss simple habits that reduce risk. Finally, we will tie the layers together into an end-to-end perspective so that model choices support the broader product and organizational goals, from experimentation to stable operations.

Machine Learning Foundations: From Features to Decisions

Machine learning converts data into decisions by optimizing a loss function under constraints. At its core are four elements: representation (features), objective (loss), search strategy (optimization), and evaluation (metrics). Supervised learning uses labeled examples to map inputs to outputs; unsupervised learning finds structure in unlabeled data; semi-supervised approaches combine both; reinforcement learning optimizes decisions via trial-and-error signals. In many organizations, supervised learning on structured data remains a workhorse because it strikes a balance between accuracy, data needs, and interpretability.

The practical workflow begins with problem framing. Are you predicting a probability, a category, a number, or a ranking? What baseline performance is acceptable given business impact and risk tolerance? Feature engineering translates raw inputs into informative signals: aggregations over time windows, domain-driven ratios, and encodings for categorical variables. Regularization (such as penalties on large weights) guards against overfitting, and cross-validation estimates generalization by simulating out-of-sample behavior. Evaluation should reflect decisions: for imbalanced classification, precision–recall and calibration can be more informative than raw accuracy.

Consider examples. A demand forecast powered by regression may reduce inventory costs while improving service levels. Anomaly detection on sensor streams can catch rare failures early by modeling typical behavior and flagging deviations. A propensity model for outreach may prioritize limited human attention for higher-impact cases. In many of these scenarios, compact models are easy to deploy on low-power hardware and retrain frequently, giving timely updates without heavy infrastructure.

How does this compare to neural networks and deep learning? Classic machine learning often excels on:

– Tabular datasets with strong human-understood features

– Modest-sized data where interpretability and speed matter

– Settings with frequent retraining and strict latency budgets

Neural networks can surpass these methods when the relationships are highly non-linear or when raw signals (images, audio, free text) carry information that engineered features cannot capture. Yet the trade-offs are real: deeper models usually require more examples, careful hyperparameter tuning, and additional monitoring. A practical approach is to start with a clear baseline, measure improvements, and escalate complexity only when evidence shows a durable gain.

Neural Networks: Differentiable Function Blocks and Design Choices

Neural networks approximate functions by composing simple transformations—linear layers followed by non-linear activations—over and over. This composition allows them to model intricate interactions: where classic models might assume additive effects or shallow interactions, a neural network can learn layered combinations of features. Training proceeds through backpropagation, which computes gradients of the loss with respect to each weight and nudges the network to reduce error. The universal approximation theorem tells us these models can represent a wide variety of functions, but capacity must be matched to data and regularization to avoid memorization.

Architecture matters. Width controls the number of features learned per layer; depth controls how hierarchical the representation becomes. Activation functions like rectified linear units and smooth alternatives shape gradient flow. Initialization affects early learning dynamics; normalization stabilizes training; optimizers determine how aggressively parameters move. Regularization techniques such as dropout, weight decay, and early stopping reduce overfitting by preventing reliance on a few fragile pathways.

Where do neural networks shine compared to traditional models? They excel when raw signals are complex, high-dimensional, and locally structured. For sequences, recurrent or attention-based components can model temporal dependencies; for images, spatial filters discover edges and textures that combine into shapes; for categorical tokens, embeddings learn dense vector representations that capture similarity. This learned representation capability often reduces manual feature engineering and can discover subtleties humans might miss.

The trade-offs are important:

– Data hunger: more parameters typically demand more labeled examples or careful augmentation

– Compute intensity: training may require specialized hardware and longer cycles

– Debuggability: intermediate representations are abstract, so explanations need auxiliary techniques

Practical guardrails help. Monitor training and validation curves to detect overfitting; use learning-rate schedules to navigate plateaus; and reserve a final holdout set for credible evaluation. When deployment constraints are tight, prune weights or quantize parameters to shrink models without large accuracy loss. When interpretability is vital, complement networks with post-hoc tools (feature attribution, counterfactual probes) and validate against domain-specific checks. In short, neural networks offer flexible function approximation, but the surrounding engineering choices determine whether that flexibility translates into reliable outcomes.

Deep Learning: Representation, Scale, and Modern Workloads

Deep learning extends neural networks by stacking many layers so the model can learn progressively abstract representations. Early layers detect simple patterns, intermediate layers combine them, and later layers synthesize high-level concepts useful for the final task. This hierarchy is particularly effective for perception and language, where structure is rich and distributed. Parameter counts can range from thousands in compact models to millions or even billions in frontier systems, and with scale come both gains in accuracy and increased operational demands.

Common architectural motifs include convolutional layers for spatial signals, sequence processors for time-dependent data, and attention mechanisms that let models focus on the most relevant parts of the input. Transfer learning further amplifies value by adapting a model trained on broad data to a specific task with far fewer labels. This reuse can dramatically reduce training time and carbon footprint compared to training from scratch, while still delivering strong performance on domain-specific goals.

Deep systems invite new considerations:

– Data pipelines must handle volume and variety: large files, sharding, streaming, and augmentation

– Training stability benefits from normalization, residual connections, and careful initialization

– Evaluation should include robustness checks against distribution shifts and adversarial noise

– Deployment planning must address latency, memory, and energy, especially for edge devices

A practical example is visual inspection in manufacturing: a deep model can learn to detect minute surface defects by combining low-level texture cues into higher-level judgments, even when defects vary in size and orientation. In speech interfaces, deep architectures model acoustic and linguistic patterns jointly, improving recognition accuracy and downstream understanding. In recommender systems, learned embeddings capture subtle affinities that evolve over time, allowing fast ranking while personalizing results.

The trade-offs are not only technical but organizational. Training cycles can be longer, requiring coordinated experiments, disciplined versioning, and reproducible pipelines. Model governance becomes more pressing: fairness, privacy, and safety reviews should accompany accuracy metrics from the start. Ultimately, deep learning offers exceptional representational power, but it pays off when matched to problems where the input complexity justifies the additional data, compute, and operational care.

Conclusion and Next Steps: Building a Cohesive AI Stack

Bringing the layers together—machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning—means aligning technique with context. Start with the question, not the algorithm: define success metrics that reflect decisions, quantify costs of errors, and identify where interpretability is essential. Establish data contracts so that upstream changes are visible and auditable. Create small, trustworthy baselines, then iterate with increasing complexity only when measurable gains survive cross-validation and holdout tests. Treat infrastructure as an enabler, not a distraction: automated data checks, reproducible training scripts, and monitored deployments reduce fragile handoffs.

A practical action plan:

– Frame the problem and choose metrics that reflect real decisions

– Build a baseline using a compact model; document assumptions and data lineage

– Run controlled experiments, escalating to deeper architectures when the task demands richer representations

– Plan for deployment early: latency budgets, memory limits, and update cadence

– Monitor in production: data drift, calibration, fairness, and performance alarms

– Close the loop with error analysis, user feedback, and periodic retraining

Comparing approaches becomes straightforward under this lens. If your data are structured and small-to-medium in size, start simple and iterate. If your inputs are visual, acoustic, or raw text, expect gains from deeper architectures and transfer learning, with an eye on compute budgets. If transparency is a hard requirement, prefer models and explanations that stakeholders can understand, or pair deeper models with rigorous interpretability checks. Across all cases, measure, document, and rehearse rollback plans so you can respond confidently to surprises.

As the ecosystem evolves, the most resilient teams combine technical depth with disciplined process. They treat the AI stack as a living system: new data arrive, models age, requirements shift. By understanding how machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning complement one another, you can choose tools that fit the task, deploy them responsibly, and maintain them with care. That alignment—between goals, data, and method—is what turns promising prototypes into dependable, real-world systems.